Henry Ho: HKSAR govt tasked to enhance national security education

本智庫副主席甘文鋒接受TVB訪問

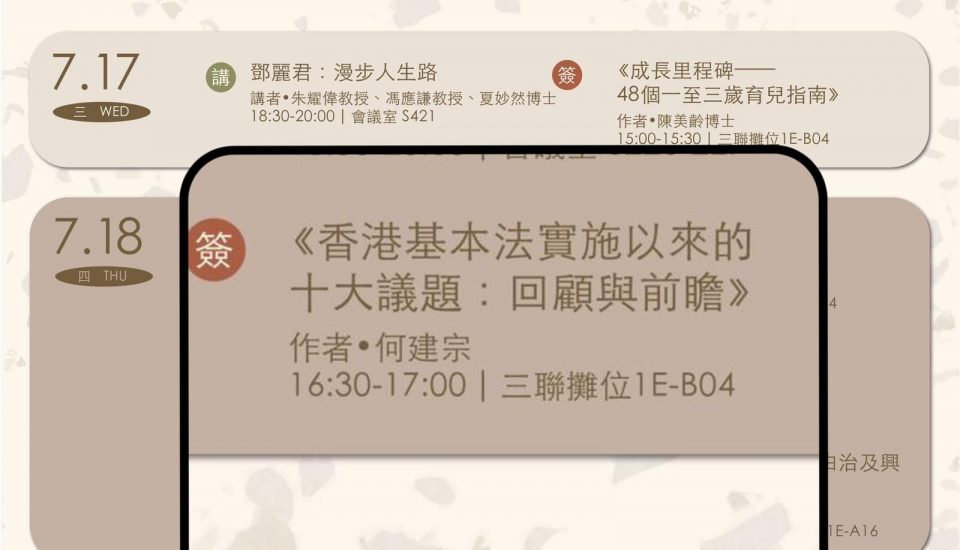

何建宗:推動兩地法律合作更上新台階

It has been more than two years since the implementation of the National Security Law for Hong Kong (NSL). Although the law has helped the city restore order from chaos, its implementation still encounters some practical challenges. The most recent example is the debate over whether Timothy Owen, a UK-based lawyer, can represent Jimmy Lai Chee-ying legally in a national security case. The public dispute over this matter also reflects, to some extent, that there is still room for improvement regarding the implementation of the NSL, especially its role in raising awareness of national security among Hong Kong youths.

According to Articles 9 and 10 of the NSL, the special administrative region government should “take necessary measures to strengthen public communication, guidance, supervision and regulation over matters concerning national security, including those relating to the internet”, as well as promote national security education in schools and universities and through social organizations, the media, the internet and other means to raise residents’ awareness of national security and of the obligation to abide by the law. The NSL has made the promotion of national security education within designated groups a legal responsibility — which was rare in Hong Kong before.

My research team has also conducted research regarding how the SAR government can learn from the experience of the Chinese mainland and Macao to effectively promote national security education among the above-mentioned four groups.

On the Chinese mainland, national security education is coordinated by the committee for safeguarding national security at different levels, with schools and teachers the main focus to conduct relevant work. Taking Guangdong province as an example, all schools adopt the same teaching and learning materials. In the way of teaching, there are both school courses and extracurricular activities online and offline. Parents are also required to take part in student activities. The various promotional channels range from State media to social media, with national education elements embodied in different forms such as articles, comics and short videos. Moreover, social organizations also use their influence and close connections with people, and hold an array of seminars and forums to enhance people’s awareness of national security.

Similarly, in Macao, national security education is coordinated by the Committee for Safeguarding National Security of the Macao SAR. Meanwhile, the Macao SAR government adopts different teaching approaches toward students of different levels. Secondary and primary students are not required to take specific national security courses. Instead, the national security elements are embedded in subjects like Character and Citizenship Education. Students of higher education need to pass mandatory courses relating to the country’s Constitution and the Basic Law of the Macao SAR. The mastery of national security knowledge is closely linked to a student’s enrollment or the career of government officers.

In Macao, social organizations — which also receive government sponsorship for national security education activities, including mainland exchange visits and youth competitions — are important forces to cultivate public awareness. Furthermore, for a long time, most of the media in Macao — whether public or private — have voluntarily upheld the principle of safeguarding national security. Many media outlets and lawmakers also take advantage of the highly interactive nature of social media to enhance the public understanding of national security.

However, in Hong Kong, there is no clear coordination mechanism for national security education. The Education Bureau (EDB) takes charge only of on-campus education, while education for other groups is the responsibility of other departments such as the Security Bureau and the Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau. In addition, the HKSAR government has not yet promulgated any specific policy documents targeting national security education other than those in schools.

Currently, some people still hold a skeptical attitude toward implementation of the NSL in Hong Kong, resulting in a weak social atmosphere for advocating national security education. The most obvious example is the inactive participation of social organizations. Compared with Macao, few organizations in Hong Kong voluntarily launch educational programs, especially those of a large scale, in terms of national security. Meanwhile, social organizations receive less support and sponsorship from the HKSAR government than those in Macao. That limits those organizations’ ability to hold large-scale activities and is not helpful for promoting national security education.

Apart from that, insufficient media publicity also affects the overall outcomes of existing national security education plans. Since implementation of the NSL, despite many media outlets that allegedly violated the law shutting down, it remains the biggest challenge for the HKSAR government to actively promote public awareness of national security risks. Few media outlets use opinion pieces to advocate the importance of national security. Neither the HKSAR government nor the media have social media accounts dedicated to disseminating national security information. By contrast, the mainland and Macao have done better in this regard, with national education content widely distributed across various social media platforms.

Faced with the increased necessity to strengthen national security education, we suggest that the HKSAR government establish a national security education promotion committee, chaired by the secretary for justice, in charge of strategy and implementation. Apart from representatives of the administrative branch, the committee should include those from schools, social organizations, the media and the internet sectors, as well as scholars and professionals from the legal and education sectors. Also, it is feasible for the Department of Justice to coordinate national security education among the wider public, with professional bodies taking the lead for implementation.

At the same time, the media should also help promote national security education, as they remain the main sources of information for most Hong Kong residents. We suggest the future promotion committee provides national security courses to senior officers of local media outlets via associations like the Newspaper Society of Hong Kong, clarifies their obligations to convey these messages to frontline reporters and undergoes the necessary supervision. Furthermore, it is advisable that the HKSAR government set up a social media account for promoting national security education, and host regular exhibitions in the long run.

We are pleased to see that solid improvements have been made by the EDB to strengthen understanding among both education professionals and students of national security issues. Starting from the 2023-24 school year, all newly appointed teachers in public sector schools, Direct Subsidy Scheme schools and kindergartens joining the Kindergarten Education Scheme are required to pass a Basic Law and National Security Law Test before they start working. The EDB also promulgated the Guidelines on Teachers’ Professional Conduct to clearly stipulate the norms of behavior required of teachers. For students, the bureau has drafted the Curriculum Framework of National Security Education in Hong Kong, which serves as the guidelines for the implementation of national security education at primary and secondary schools.

In conclusion, with implementation of the NSL, the HKSAR government is tasked to enhance national security education, especially for the designated “four groups”, in an all-around way. It is time the HKSAR government put forward more detailed strategy and implementation plans for national security education, including establishing a promotion committee, to better fulfill its legal duties.

The author is a member of the Beijing Municipal Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, and founder and chairman of One Country Two Systems Youth Forum.